Earth Has a Second Moon — Well, a Quasi-Moon

Updated July 24 2023, 2:08 p.m. ET

Growing up, you probably learned that unlike other planets, Earth only has one moon; however, it turns out that isn't actually the case — planet Earth actually has a second moon, at least for the time being. More specifically, we have a quasi-moon.

But how was planet Earth's second moon discovered? Where is it and what does it look like? Is it visible without fancy equipment, or can you see it with the naked eye?

Will humankind ever venture to this second moon?

You likely have quite a few questions regarding this "second moon," which is named Kamoʻoalewa, after being spotted with a NASA telescope. We have all the details on this discovery for you.

"The natural question that arises is: what is Kamo’oalewa’s origin? The answers are speculative," reads the report which was published in Nature. "One possibility is that it was captured in its Earth-like orbit from the general population of NEOs."

"Its low eccentricity and inclination are, however, rather atypical of such captured co-orbital states found in numerical simulations," it continues.

Keep reading for more on this shocking discovery.

How was Earth's second moon discovered?

Earth's quasi-moon, Kamo’oalewa, was discovered in 2016. According to TIME, it measures at less than 50 meters across, and orbits Earth in a corkscrew motion, traveling up to 100 times the distance our regular moon does.

“It’s primarily influenced just by the sun’s gravity, but this pattern shows up because it’s also — but not quite — on an Earth-like orbit. So it’s this sort of odd dance,” University of Arizona graduate student, Ben Sharkey, who wrote the report, told TIME.

Kamo’oalewa is assumed to be a piece of an asteroid or the original moon, which somehow synched into orbit with planet Earth. It appears more dimly-lit than most moons, and was first discovered with a NASA-run telescope in Hawaii. It was then magnified with a monocular telescope that shed a little extra light on it.

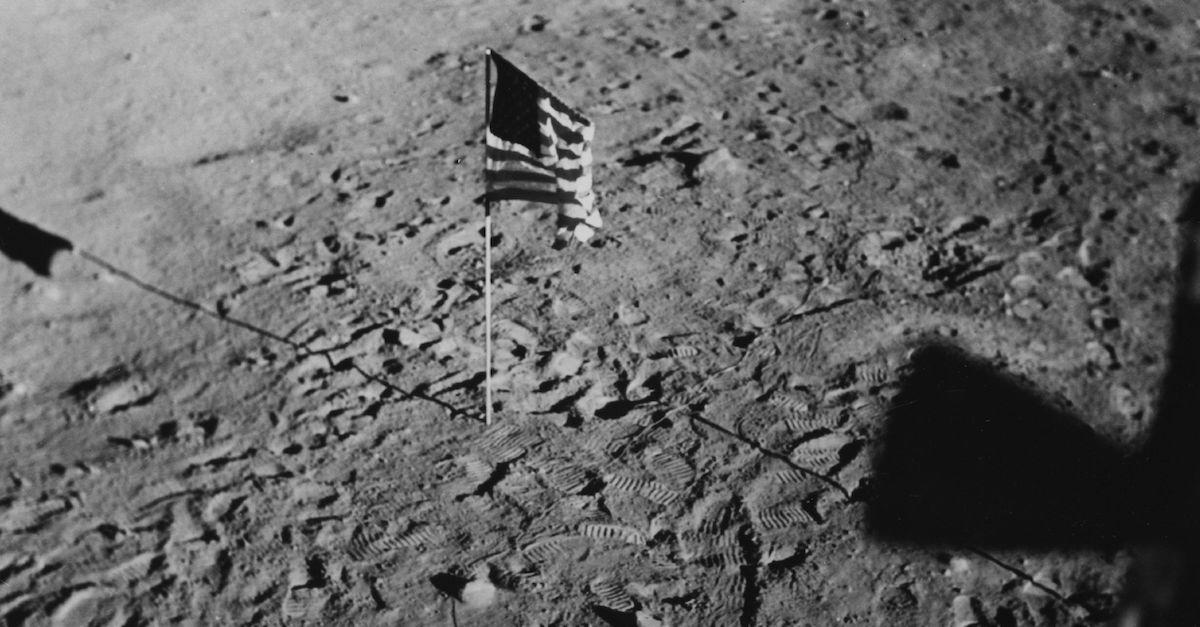

It has similar samples to what was brought back from the moon from a mission in 1971, so if it is part of the moon, it's because it was bombarded by another space rock.

“Visually, what you’re seeing is weathered silicate,” Sharkey told TIME. “The eons of exposure to space environment and the micrometeorite impacts, it’s almost like a fingerprint and it’s hard to miss.”

“We see thousands of craters on the moon, so some of this lunar ejecta has to be sticking around in space," he added.

But scientists are pretty sure it's only temporary. Kamo’oalewa might only be here for a few hundred more years before it stops orbiting Earth. Its trajectory is "unstable," and it will likely break out of the orbit and travel through space after 300 years or so.

Sometimes our actual moon looks bigger than it is — here's why.

So our second moon is only a quasi-moon, and it won't be orbiting with us forever. But our first moon is actually pretty fascinating. Not only has it orbited our Earth for billions of years, but it also sometimes makes itself look bigger because of a phenomenon called the moon illusion. That means it occasionally looks much bigger than it is — despite the fact that it's stayed the same size — because of its proximity during its orbit.

In reality, though, the moon is moving farther away from planet Earth. About 4.5 billion years ago it sat 14,000 miles from planet Earth, but it's been drifting 1.48 inches away from us each year, according to BBC News.

One day in the far off future, our second moon will no longer be in orbit with Earth, and the actual moon will be significantly farther away — though it doesn't seem as though that will happen in our lifetime.

This article, originally published on Dec. 28, 2021, has been updated.